CNIL fines Google & Amazon €135m on cookie fails

Lessons from French data protection authority's record fines on Google, Amazon for basic cookie failures

Originally published by Thomson Reuters © Thomson Reuters.

Lessons from French data protection authority’s record fines on Google, Amazon for basic cookie failures

The December 2020 enforcement actions by the French data protection authority, the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL), concerning Google and Amazon are short, to the point and a clear statement of intent on jurisdiction. There are lessons to be drawn from both decisions.

CNIL alleged that both Google and Amazon services dropped certain advertising cookies for users in France, visiting google.fr and amazon.fr respectively, without the required prior consent, with (very) insufficient prior information, and without a true ability to refuse them. The regulator alleged that this was in breach of the French implementation of the e-Privacy Directive contained in la Loi Informatique et Libertés (LIL).

The fact that advertising cookies were dropped before any consent was received was not really disputed, but the companies argued without success that their notice provisions were better than CNIL gave them credit for. This part does not lead to a particularly surprising decision.

In both cases, however, the companies argued that France and CNIL did not have jurisdiction, and that the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and its cooperation and consistency mechanisms should apply to their respective enforcement actions. Part of their argument was that:

- there was no separate national implementation of the e-Privacy Directive in France; it was contained in the national Data Protection Act – this would not be an available argument in the UK, for example; and

- that the two European regimes were so connected that the actions should proceed under the GDPR’s one-stop shop mechanism.

For Google, this meant the action should be passed to the Irish Data Protection Commission and be against Google Ireland Ltd (Google Ireland), its relevant controller for the European Economic Area (EEA), and not Google France SARL (Google France).

For Amazon, this meant it should be passed to the Luxembourg National Commission for Data Protection and be against Amazon Europe CORE (Amazon Luxembourg), its relevant controller for the EEA, and not Amazon Online France SAS (Amazon France).

National regulators will continue to claim cookie jurisdiction

Both Google and Amazon argued that the procedural rules of the GDPR and the one-stop shop should apply, not the LIL. CNIL disagreed, with four main arguments.

- The e-Privacy Directive’s own art 15a states that ‘member states shall lay down the rules on penalties’ applicable to infringement of national implementation, and these were contained in the LIL.

- They referred to GDPR’s final recital (Recital 173), confirming that GDPR did not cover specific obligations in the e-Privacy Directive which also concern the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms regarding the processing of personal data, including the obligations on the controller and the rights of natural persons.

- They referred to two on-point statements from the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). In the EDPB’s Opinion 5/2019 of March 12, 2019, tellingly entitled ‘Opinion 5/2019 on the interplay between the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR, in particular regarding the competence, tasks and powers of data protection authorities’, the EDPB states: ‘The GDPR [cooperation and consistency mechanisms available to data protection authorities] do not apply to the enforcement of the provisions contained in the ePrivacy Directive as such.’ In the EDPB’s ‘Statement on the ePrivacy Regulation and the future role of Supervisory Authorities and the EDPB’ of November 19, 2020, the EDPB argued strongly for GDPR’s one-stop shop mechanism to be introduced in any future e-Privacy Regulation.

- CNIL also made the very practical point that the regulatory authority under the e-Privacy Directive need not be the member state’s data protection authority; indeed it is often the telecommunications regulator, which is not a member of the EDPB.

Material competence settled in each case, CNIL moved onto territorial jurisdiction. CNIL again noted that France’s LIL applied, that GDPR’s one-stop shop did not apply, and decided that dropping the cookies in question had taken place respectively in the context of the activities of Google France (the French establishment of the Google group) and Amazon France (the French establishment of the Amazon group). CNIL therefore had territorial jurisdiction in each case.

CNIL decided, in essence, that France was granted jurisdiction by the e-Privacy Directive and CNIL, in turn, by the French national implementing law.

Ring-fencing privacy liability is not always easy

There is a clear benefit in having a business recognised throughout the world by the same name, even a single word, regardless of whether the end provision is by a (possibly overseas) entity or a local group member, agent, franchisee or other presence.

The decision against Google shows that, at least in the data protection arena, this blurring of control and personalities can sit badly with the sometimes delicate legal and regulatory structure put in place to ring-fence liabilities.

Google’s Controller

Following certain CJEU decisions, large U.S. entities such as Facebook and Google have expended considerable energy empowering a particular EEA entity to be their group’s true controller for GDPR, in place of the U.S. parent. The Googles accordingly argued that Google Ireland was solely responsible as controller for the choice of cookies used and data collected in France, and that Google LLC was simply a processor.

CNIL in effect agreed that Google France had little to do with the actual cookies, and that Google Ireland was a controller here.

CNIL did not agree with Google LLC’s processor role, however, identifying, for example, Google’s matrix organisational structure and that Google LLC was just as represented in the bodies deciding on the processing in question and, crucially, determined the advertising purpose of that processing.

CNIL also noted that Google Ireland’s data protection officers (DPOs) were located in California and were employees of Google LLC. An overseas data protection officer may not be optimal, but it is not illegal, and a data protection officer can act for more than one entity.

CNIL also noted that, apparently from the Googles’ own statements in a hearing, ‘le groupe GOOGLE a fait ce choix afin que le DPO de la société GIL soit au plus près des décideurs de l’entreprise’ – that the Google group had made this choice so that Google Ireland’s data protection officers would be closer to the decision makers. In other words, the decision makers were in the United States [para 62].

CNIL therefore decided that Google LLC determined purposes and means and was a joint controller with Google Ireland.

Amazon’s Controller

In the Amazon case, CNIL agreed that Amazon Luxembourg was the controller in respect of dropping the cookies in question, not Amazon France.

e-Privacy Directive then GDPR

In the Amazon case, CNIL noted that there could be situations where the e-Privacy Directive (and implementing laws) might apply to the use of cookies and then the GDPR might apply to the processing of personal data resulting from use of those cookies, and then the one-stop shop mechanism would apply.

Substance not form

It is worth noting here that the Google entities had partly relied on an agreement naming Google LLC as processor. This is another data point confirming that, as in the employment context, privacy roles will be determined by looking at the substance of the relationships and not simply take what the parties have set out in a contract at face value.

The breaches were avoidable

On the facts set out by CNIL, there is little surprising about the finding of breach: advertising cookies were dropped before consent was obtained. That the information provided, and right to refuse, were poorly executed also seems incontestable. Amazon even had a cookie notice in certain situations stating that the visitor’s use of the website constituted consent; that practice has been abandoned by most practitioners for some time. Amazon tried to run a defence based on the uncertainty on cookies between member states, and the lack of compliance by many other French websites, but the fact that advertising cookies were dropped before consent meant these points were rapidly dealt with.

Future e-Privacy Regulation

These cases demonstrate that regulators will continue to claim national jurisdiction over cookies unless and until their hands are tied by a new law. The EDPB’s November 2019 statement recognises this in pushing for GDPR’s cooperation and consistency mechanism in a future e-Privacy Regulation, to prevent ‘fragmentation of supervision, procedural complexity, as well as lack of consistency and legal certainty for individuals and companies.’

France’s incentivising fine structure

Google LLC was fined 60 million euros, Google Ireland 40 million euros, and Amazon Luxembourg 35 million euros, which are large sums regardless of how they compare to respective revenues. (CNIL notes that Google LLC’s 2019 revenue was $160 billion, Google Ireland’s 2018 revenue was 38 billion euros, and Amazon Luxembourg’s 2019 revenue was 7.7 billion euros.)

It is, however, the injunction-related sanction that is of note, under art 20 of the LIL, after a three-month grace period to become compliant, there is a fine of 100,000 euros for every day of non-compliance.

Single set of rules

These cases were easy for CNIL given the clear evidence that advertising cookies were dropped prior to any consent. Cookie tools are not always the easiest to use, but they have improved significantly in recent years and it is therefore highly surprising that such enormous and sophisticated cloud-based organisations could make this simple error. The jurisdictional arguments simply clarify the need for a single set of rules on cookies and similar technology across the EEA (and indeed the UK).

Robert Baugh, Founder & CEO, Keepabl

Produced by Thomson Reuters Accelus Regulatory Intelligence, 16-Dec-2020

Related Articles

News & Awards

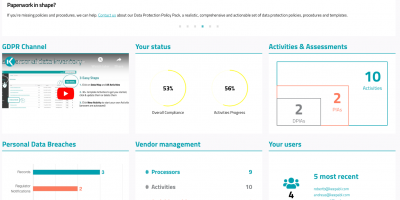

Keepabl announces new design & new Dashboard!

Keepabl announces new design & GDPR KPI Dashboard! It’s always difficult to change a design you’ve put your heart into and that customers give you great feedback about. It’s such…

News & Awards

Legal Monster becomes a Privacy Stack Partner

Legal Monster becomes a Privacy Stack Partner We’re delighted to welcome Legal Monster as Privacy Stack Partners! Cookies & Consent A key part of an organisation’s Privacy compliance – and…