October Privacy Roundup

Here's our newsletter on key developments from September that affect your operational Privacy Governance. We sent this early October and if you'd like this content in your inbox, just subscribe at the bottom of any page.

We’ve lots of practical news for you again this month on the consistent themes of children, biometrics, AI, transfers and enforcement with some news on processing agreements (the other DPA).

First, we have to start with transfers and an adequacy decision under UK GDPR for the USA! Well, actually it’s an Extension. No, it’s a Bridge. No, it’s an Adequacy Decision. Regulation. OK, it’s a Bridge.

UK-US TRANSFERS – WE HAVE A BRIDGE!

What is it?

- The UK-US ‘Data Bridge’ will take effect on 12 October 2023.

- While US entities who’d self-certified against the EU-US DPF have been able to certify against the Data Bridge since July, that can’t be relied on until 12 October.

- From 12 October 2023, UK entities can rely on the Data Bridge as the adequacy decision under UK GDPR that allows them to transfer personal data to US entities who are on the UK Data Bridge list and who comply with the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) Principles.

- It’s not a standalone adequacy decision or framework, it’s an extension to the EU-US DPF so your US data importer first must self-certify against the EU-US DPF and then also to the UK-US Data Bridge. They must appear on the DPF List maintained by the DoC and that List needs to show they’re also certified against the UK-US Data Bridge.

Joe Jones, now with the IAPP, previously Deputy Director International Data Transfers at the DCMS, has a nice post (he’s well worth following on LinkedIn) as a way into the various documents from UK Gov and commentary by the IAPP. Also helpful are the US DoC FAQs.

STOP PRESS: On an IAPP webinar 12 October 2023, senior members of the UK and US governments and civil services confirmed that the UK-US Data Bridge is an independent decision that would continue even if there were to be a Schrems III taking down the EU-US DPF under EU GDPR, and the US would continue to operate the DPF even after a potential Schrems III.

UK ICO’s Opinion on the Bridge

The UK ICO’s opinion on the Data Bridge, while supportive, states that: ‘there are four specific areas that could pose some risks to UK data subjects if the protections identified are not properly applied.’

Those 4 areas are:

- ‘The definition of ‘sensitive information’ under the UK Extension does not specify all the categories listed in Article 9 of the UK GDPR.’ So, UK organisations ‘need to identify biometric, genetic, sexual orientation and criminal offence data as ‘sensitive data’ when sending it to a US certified organisation so it will be treated as sensitive information under the UK Extension’. [Ed: aren’t we calling it a Bridge?]

- ‘For criminal offence data, there may be some risks even where this is identified as sensitive because, as far as we are aware, there are no equivalent protections to those set out in the UK’s Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974.’

- ‘The UK Extension does not contain a substantially similar right to the UK GDPR in protecting individuals from being subject to decisions based solely on automated processing which would produce legal effects or be similarly significant to an individual. In particular, the UK Extension does not provide for the right to obtain a review of an automated decision by a human.’

- ‘The UK Extension contains neither a substantially similar right to the UK GDPR’s right to be forgotten nor an unconditional right to withdraw consent. While the UK Extension gives individuals some control over their personal data, this is not as extensive as the control they have in relation to their personal data when it is in the UK.’

Now, particularly given the advances made by the USA, the decision already in place under EU GDPR, and the size of digital trade between the UK and US (see Joe Jones’s post), we certainly do not want to question the adequacy decision. But those are pretty significant areas and a ready list for a legal challenge if ever one arose.

When to use the Data Bridge

The Bridge will be there in a few days and, under GDPR, you only go to Art 46’s other safeguards (in practice that’s SCCs, or the UK’s IDTA or Addendum to the SCCs) if there’s no adequacy decision under Art 45. So we recommend you use the Data Bridge if it is available – technically you should.

Does this mean no more SCCs for the USA?

You can only use the Data Bridge if your US counterparty is on the List for both EU-US DPF and the UK-UK Data Bridge. If not, you need to use SCCs (OK the UK Addendum, no-one really uses the IDTA).

If your counterparty is on the List correctly, we’d still recommend having the UK Addendum to the EEA SCCs in place alongside the Data Bridge to specify the transfers, security measures etc and your ‘wrapper’ agreement can say that the Addendum/SCCs will only be the transfer mechanism if the Data Bridge fails.

That way you detail your transfer, you cover off your Art 28 Processing Agreement obligations (which you don’t by using the IDTA) and you’re covered if something odd happens to the Bridge or DPF.

Key Takeaways

- Review your transfers to the USA.

- Identify which US counterparties are on the List.

- Review your transfer arrangements and update them to refer to the Data Bridge.

Transfers are often between controllers and processors, which takes us neatly onto whose obligation it is under Article 28 GDPR to have a written contract in place. What’s your answer? Don’t cheat by reading ahead….

STOP PRESS: The first legal challenge to the EU-US DPF failed on 12 October 2023 as the claimant, a French MEP, had not shown the urgency or particular harm to himself, so the court did not need to look at the other parts of the test for issuing an injunction preventing the DPF taking effect.

PROCESSING AGREEMENTS (OR ‘THE OTHER DPAs’)

Whose obligation?

The EDPB set out its position on this, very clearly, in para 103 of Guidelines 07/2020 on the concepts of controller and processor in the GDPR, Version 2.1, Adopted on 07 July 2021 (our emphasis):

‘Since the Regulation establishes a clear obligation to enter into a written contract, where no other relevant legal act is in force, the absence thereof is an infringement of the GDPR. Both the controller and processor are responsible for ensuring that there is a contract or other legal act to govern the processing. Subject to the provisions of Article 83 of the GDPR, the competent supervisory authority will be able to direct an administrative fine against both the controller and the processor, taking into account the circumstances of each individual case.’

And, on 29 September (hats off to Peter Craddock, another good person to follow on LinkedIn, for posting about this decision) the Belgian DPA agreed, held that the obligation to have a processing agreement in place under GDPR is on both parties, the controller and the controller.

Prior Effective Date irrelevant

A more interesting practical titbit from the case is on Effective Date. It’s relatively common in contracts to state that the Effective Date of a contract is earlier than the date you sign it – you’re not backdating it, you’re saying you’ve papered your relationship after it started. That’s what happened in this case.

But, while that may have put in place contractual rights and obligations between the parties from the earlier date, it didn’t make up for putting a processing agreement in place later than it should have been under GDPR – which makes sense.

Key Takeaways

- If you’re a controller, review your list of processors to check you’ve a processing agreement in place with them all.

- If you’re a processor, review your list of processors to check you’ve a processing agreement in place with them all.

- Indeed if you’re a processor, you should make sure your current standard processing agreement you give controllers is nicely up to date.

ENFORCEMENT

Fines aren’t always reduced on appeal

The Norwegian Privacy Board upheld the DPA’s NOK 65 million fine (just under £5m) on Grindr for sharing data without a legal basis. It’s an interesting case of a fine being maintained on appeal.

UK ICO reprimands Ministry of Justice

On 8 September the UK ICO issued a reprimand to the MoJ in line with its policy generally not to fine the public sector. However, this case was pretty impactful as the ICO notes:

‘In this case, the details of parties in an adoption process were disclosed to the birth father, despite a court judge directing that he should be excluded from the proceedings on the grounds that he posed a risk to the family concerned. The cause of the incident was the removal of the cover sheet from the front of the adoption file, which the MoJ stated was a practice that had been developed locally at #########, a process that did not reflect national practice. Furthermore, the MoJ stated that the use of the cover sheet was not a written policy but was communicated by word of mouth.’

Key Takeaways

- Review your handling of sensitive or confidential data and data you don’t want to make a mistake with.

- Review how you’re sharing personal data and if you’ve an appropriate legal basis.

- Check to see what procedures are actually being followed.

- Raise awareness and train as appropriate to change unwanted practices or reinforce best practice.

CHILDREN

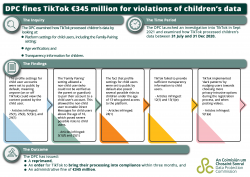

DPC €345m fine on TikTik for 5 months non-compliance on children’s data

How strange is it when a €345m GDPR fine isn’t shocking news? Imagine if the FCA issued that size of fine.

The DPC created a helpful infographic of the TikTok case and fine:

The image is great and the DPC has a very clear press release. Given the decision is as big as the fine, we’ll just highlight:

- TikTok had not made children’s data settings private by default in many situations,

- there was no agreement on the DPC’s draft decision, particularly with objections from Italy and Berlin DPAs, and so it went to the EDPB, and

- Ireland’s DPC hit TikTok with this huge fine for its actions over children’s personal data in just 5 months from 31 July 2020 to 31 December 2020.

That’s effectively €69m per month, which makes the UK ICO’s 2023 fine of £27m on 4 April 2023 look very low also related to children’s data and related to a 27 month period from May 2018 to July 2020, ending when the DPC’s period started.

And the US FTC’s fine on TikTok of $5.7m, in 2019 under COPPA, now looks pretty small.

Key Takeaways

- Check if you process childrens’ personal data.

- If you do, ensure your Privacy Policy is up to date and clear for the readership.

- If you do, review your practices with a clear Data Protection by Default and by Design lens.

The children’s aspect of this TikTok fine leads us onto events in California.

CA court strikes out The California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act

In a decision on 18 September 2023, a Judge in the United States District Court, Northern District Of California, San Jose Division granted an injunction preventing enforcement of the CAADCA as it ‘likely violates the First Amendment’.

The CAADCA was closely modelled on the UK ICO’s statutory Code of Practice on Age-Appropriate Design.

While the First Amendment argument clearly doesn’t wash in the UK, the reason we’re covering this here is as another example of how important local law, practice and culture are in data protection.

It’s illuminating to see that the person leading NetChoice’s efforts to stop the CAADCA is reported as saying: ‘We look forward to seeing the law permanently struck down and online speech and privacy fully protected,’ when at least here in the UK and Europe there is no such thing as entirely free speech, it’s tempered by various laws, such as against inciting religious or racist hatred and violence and there have been moves to regulate online harm to children in the EU and now UK.

Elizabeth Denham on Children’s Data and Codes etc

For those working with children’s data, the IAPP recently hosted a great webinar with the former UK Information Commissioner on this very topic, well worth listening to, and there are IAPP articles by the same team here and here.

All of this brings us nicely to news about the UK’s Online Safety Bill.

UK ONLINE SAFETY BILL

Ironically, in the same month that the CAADCA is shot down by a consortium of tech giants (NetChoice ‘counts Amazon, Meta and Google as members’) those same tech giants are named on lists in the EU’s new Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, which impose obligations on such operators to look at harmful content and more, and the UK’s Online Safety Bill has passed all stages and is now ready for Royal Assent.

The Bill has been re-focussed on illegal and specifically – as in specified – harmful content rather than the more vague ‘legal but harmful’ content, but there are many key points to note, including these 4 most interesting areas.

1. The encryption backdoor is still there, though in the House of Lords debates, the Minister said that Ofcom would only issue an order when the technology was available to scan for particular content without harming Privacy. We paraphrase so here are the actual words – that aren’t in the Bill:

“Ofcom can require the use of a technology by a private communication service only by issuing a notice to tackle child sexual exploitation and abuse content under Clause 122. A notice can be issued only where technically feasible and where technology has been accredited as meeting minimum standards of accuracy in detecting only child sexual abuse and exploitation content. Ofcom is also required to comply with existing data protection legislation when issuing a notice under Clause 122 and, as a public body, is bound by the Human Rights Act 1998 and the European Convention on Human Rights.

When deciding whether to issue a notice, Ofcom will work closely with the service to help identify reasonable, technically feasible solutions to address child sexual exploitation and abuse risk, including drawing on evidence from a skilled persons report. If appropriate technology which meets these requirements does not exist, Ofcom cannot require its use.”

2. Risk assessments are there, and are to cover illegal content (section 8), child risk (s10) and adult risk (s11), with the largest providers to report and publish.

3. Categorisation of providers moves from a test of size “and” functionality to a test of size “or” functionality, so do review if you’re covered.

4. New crimes include AI deepfakes. There are 4 new crimes on intimate images abuse, to replace existing crimes, and they cover manufactured or deep-fake images for the first time (see page 127).

MONITORING AT WORK

UK ICO launches new guidance on monitoring at work

A new survey commissioned by the ICO reports that ‘70% of the public would find it intrusive to be monitored by an employer’.

And the UK ICO’s new Guidance on Employment practices and data protection − Monitoring workers landed 3 October, just making this newsletter. It’s a hot topic internationally as you’ll see below, and covers problems with consent at work, use of biometrics, transparency and more.

The ICO has a list of recommended steps an organisation must take if it’s looking to monitor workers:

- ‘Making workers aware of the nature, extent and reasons for monitoring.

- Having a clearly defined purpose and using the least intrusive means to achieve it.

- Having a lawful basis for processing workers data – such as consent or legal obligation.

- Telling workers about any monitoring in a way that is easy to understand.

- Only keeping the information which is relevant to its purpose.

- Carrying out a Data Protection Impact Assessment for any monitoring that is likely to result in a high risk to the rights of workers.

- Making the personal information collected through monitoring available to workers if they make a Subject Access Request (SAR).’

Norway’s Guidance on Monitoring of employees’ use of electronic equipment

Norway is such an interesting case because it has specific laws on employers’ rights to access (or rather not access) employees’ emails – including when an employee leaves.

As Datatilsynet notes in its guidance:

‘In Norway, we have separate regulations that apply to employers’ access to employees’ e-mail boxes and other electronically stored material. The regulation prohibits the monitoring of employees’ use of electronic equipment. In this guide, we will consider when the ban on surveillance applies and what exceptions there are.’

‘The e-mail regulations § 2, second paragraph

“The employer does not have the right to monitor the employee’s use of electronic equipment, including the use of the Internet, unless the purpose of the monitoring is

a. to manage the company’s computer network or

b. to uncover or clarify security breaches in the network.”’

There have been cases in Norway when, for example, employers redirect an ex-employee’s email, that are surprising to a UK practitioner because of these specific laws. It’s a great example again of needing to look beyond GDPR and at other local laws.

UK ICO BIOMETRICS GUIDANCE

The UK ICO launched a consultation on draft Guidance on the use of biometrics. We’ll just link you to our article on this for Thomson Reuters Regulatory Intelligence which, though written for Finance, gives you all the links and details you need to know.

All about purpose

GDPR defines ‘biometric data’ but whether or not that is special category personal data depends on your purpose – are you using it to identify the individual?

This all sounds like it’s splitting hairs but, in practice, it’s likely to be moot because you probably are using biometrics to identify individuals – why else would you use it in a commercial setting?

You’re likely using it for office access. And if you are, read this from the UK ICO’s new HR Guidance. You need to give an alternative:

‘If you are relying on biometric data for workspace access, you should provide an alternative for those who do not want to use biometric access controls, such as swipe cards or pin numbers. You should not disadvantage workers who choose to use an alternative method. It is likely to be very hard to justify using biometric data for access control without providing an alternative for those who wish to opt out.’

Risk

Don’t have blind faith in accuracy and efficiency of your proposed solution, fingerprints don’t always work, face recognition can be wildly inaccurate, voice recognition can be deepfaked, and emotion recognition – don’t get us started.

And don’t stop at GDPR.

- If you’re in the UK but have global footprint, the main risk will be state laws like Illinois’s BIPA and similar laws in Texas and elsewhere.

- Biometric solutions likely use AI, so laws such as New York’s AI-in-recruitment law come into play.

- Check the definitions in each applicable law, they may overlap but they won’t be the same.

Legal Basis

Consent isn’t likely to work in an employment setting. The UK ICO gives interesting support on using prevention and detection of unlawful acts but you’ll need to check your national DP laws for national special category exemptions.

Key Takeaways

Here are our 8 action points from our article:

- Audit where the business wishes to use — and already uses — biometric data in the organisation anywhere in the world. Identify the purpose of each processing activity and all relevant context.

- Identify relevant, applicable laws.

- If the business is covered by UK or EU GDPR, or a modern comprehensive Privacy law in a US state, carry out a data protection impact assessment or risk assessment.

- Decide on the appropriate legal basis for each of those processing activities:

- For example, consent may be the only option in some cases (in which case a different option must be provided to individuals who do not consent) and prevention and detection of unlawful acts may be appropriate in others.

- Where the firm does not use consent, document why the processing of special category biometric data is ‘necessary’ for your chosen legal basis (such as the prevention and detection of crime and for reasons of substantial public interest).

- Document how the firm’s use of biometric data is targeted and proportionate ‘to deliver the specific purposes set out in the condition, and that you cannot achieve them in a less intrusive way’.

- Document how the firm has investigated how the solution avoids bias in this particular situation with these particular individuals.

- Make sure, as required, that the firm has an appropriate policy document for UK GDPR and appropriate policy for BIPA.

- Provide prior information to individuals to meet the firm’s transparency obligations.

We know your business wants to use all this, read our article, follow the links and build your accountability audit trail carefully.

KEEPABL SHORTLISTED FOR MORE AWARDS

We’re delighted that we’re in amongst it again, this award season.

#RISK

In a double whammy, both Keepabl and our CEO Robert Baugh are shortlisted for the 2023 #RISK Awards.

- Keepabl’s Privacy Kitchen is shortlisted for Best Innovation in Training and Development

- Robert Baugh is shortlisted for RISK Leader

PICCASO Europe

Our CEO, after winning Privacy Champion at the 2022 PICCASO Awards, which were UK-focussed, is again shortlisted for the expanded PICCASO Europe Awards 2023 – for Privacy Writer / Author 2023.

Fingers crossed for November and December!

SIMPLIFY YOUR COMPLIANCE WITH KEEPABL

Need to upgrade (or even establish) your RoPA into something that’s easy to create and maintain? Need automated Breach and Rights management?

Do contact us to see for yourself, book your demo now!

Related Articles

Blog

Seamless File and Attachment Management with Keepabl

Keepabl’s File Library is super helpful. You can upload all documents relevant to your data protection compliance and link them to the relevant Record in Keepabl, such as an Activity,…

Blog

VCs: how Keepabl's Privacy Management SaaS supports your portcos in the unicorn race

Venture Capital investors invest a finite sum of money into a finite number of businesses and aim for one portfolio company to ‘return the fund‘. It’s just the way the…