UK Consultation on Data Protection Reforms 2021

The DCMS consultation has just closed – what were the responses?

On 10 September 2021, the UK’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) launched Data: a new direction, a consultation seeking responses on a wide range of proposed changes to UK data protection laws and regulation. it included a Consultation document and an Analysis of expected impact.

The consultation closed on 19 November 2021. A lot’s been written on the proposals, so we’ll just summarise them and point you to some of the responses we’ve seen:

- we’ll start with analysis from legal experts Bird & Bird and Herbert Smith Freehills and UPDATE: we’ve now also included Hogan Lovells,

- we’ll then look at industry, and the response from BRC, the trade association for UK retailers,

- then the UK ICO‘s own response, and

- the response from the Independent Commissioner for Biometrics and Surveillance Cameras (who hadn’t even been told his 2 roles were up for absorption into the ICO!),

- before looking at our founder‘s personal response, and

- ending with Keepabl‘s position.

Honestly, you have to read this. And we’re talking to you, DCMS.

First, why?

Why is the British government looking to change the rules for British organisations and UK data subjects right now? We’ve recently come out a long roller-coaster Privacy ride including Brexit, GDPR applying, the looooooong and winding road to adequacy, and we’re stuck into Schrems II. On the wider economy, we’re coming out of the biggest recession for 300 years and dealing with ongoing Brexit impacts.

Launching the consultation, the government stated:

‘Outside of the EU, the UK can reshape its approach to regulation and seize opportunities with its new regulatory freedoms, helping to drive growth, innovation and competition across the country. The UK needs agile and adaptable data protection laws that enhance its global reputation as a hub for responsible data-driven business that respects high standards of data protection.’

Wow, ambitious! Exciting! Terrifying! The proposals must be ground-breaking to achieve these aims. What previously unknown magic was in there, that will set the UK apart as such a beacon for the world to follow?

If you can sense a sarcastic tone, you’re not wrong.

The Proposals

The Conjurer 1500, painting after Hieronymus Bosch

(Museum: Israel Museum), details

The Consultation document is 146 pages long, which is fair as this is a very sensitive and mission-critical topic for all concerned. After a Ministerial foreword, it’s split into:

- an Introduction

- Chapter 1 – Reducing barriers to responsible innovation

- Chapter 2 – Reducing burdens on businesses and delivering better outcomes for people

- Chapter 3 – Boosting trade and reducing barriers to data flows

- Chapter 4 – Delivering better public services, and

- Chapter 5 – Reform of the Information Commissioner’s Office

The Consultation sets out its case for reform, proposals to effect the reform, and asks your opinion on specific questions on those proposals, in a ‘Strongly agree’ through to ‘Strongly disagree’ basis, inviting you to put forward evidence and reasoning for your answers.

Bird & Bird

This international law firm is perhaps the leading firm on data protection in Europe. In a clear, brief, tabular summary, the firm analyses various aspects of the Consultation. It’s a blog not a formal response, and it takes an understandably dispassionate approach of simply describing the impact on the current regime. That in itself is very interesting.

However, on Accountability, the firm states (our emphasis):

‘The departure from the existing GDPR framework for accountability is puzzling. DCMS’ stated reason for the proposed reform is that current accountability obligations place a “disproportionate administrative burden” on organisations, yet its proposals involve replacing existing accountability requirements with other very similar (and no less burdensome) obligations. With the exception of the higher threshold for breach reporting, all other accountability requirements have been replaced with a different compliance requirement, often with the choice of the format left to organisations. This would likely create more work for organisations, who would need to assess whether their existing GDPR documentation matched the new UK requirements. For example, there is a suggestion that GDPR-DPOs could not serve as the person responsible for the privacy management programme (as the independence they require for GDPR purposes would – implicitly – disqualify them from this new role), so that an organisation which chose to retain its DPO would need to appoint an additional data protection professional [164]. The proposals seem to diverge from the GDPR without providing any discernible benefit to organisations in the UK.’

Herbert Smith Freehills

The legal giant has a longer summary blog of the DCMS proposals (again it should be noted it’s not a response) and they incorporate parts of the ICO’s response, which is useful. ‘Herbies’ is equally sanguine on the savings for small and medium businesses, in particular, from the proposals on how organisations will manage their compliance (again, our emphasis):

‘Organisations have already invested considerable time and cost in their own GDPR compliance in recent years. Whilst the proposed reform is stated to “offer improvements within the current framework” and is earnest in theory, it remains to be seen whether the proposed divergence from the existing (EU-based) regime will in fact realise the benefits suggested by the DCMS, and whether it really is more “business friendly” in practice.

The proposals appear to be skewed more heavily towards benefiting smaller organisations in particular, which have historically struggled with the burden of data protection compliance. However, with the added administrative layer for organisations (first having to assess their current EU GDPR compliant practices against any new UK requirements, as well as exercise a greater level of discretion as to how best to comply), there is a risk that the reform may prove to be no less burdensome overall, at least at the outset.’

And, later:

‘Whilst the proposed changes to the existing framework are relatively significant, in a marked deviation from the EU GDPR requirements, the perceived benefit to small and micro-businesses of “reducing burdens”, may well not be realised in practice. In particular, it is possible that the proposal simply substitutes existing accountability requirements, with similar (but no less onerous) ones, adding a further administrative layer for organisations; first having to assess their current EU GDPR compliant practices against any new UK requirements, as well as exercise a greater level of discretion as to how best to comply (albeit the DCMS has suggested the ICO may provide related guidance in order to assist).’

Hogan Lovells

[UPDATE 24/11/21] Hogan Lovells is another top-tier international law firm and the firm of leading Privacy lawyer Eduardo Ustaran. We’ve updated this post to include their 8-page formal response. It’s very diplomatic as one would expect, very much like the ICO’s own response. However, it’s not a summary, it does take positions.

The response is very supportive of the UK leading the way ‘in designing the most effective data protection regime in the world‘, but when you read it carefully, it doesn’t seem all that supportive of many of the actual proposals, particularly the big ones.

For example, while the response agrees that Article 22 needs updating and does argue for a broadening of situations when solely automated decisions can be made, it also recommends introducing a monitoring obligation and retaining the right to human review. It’s a very reasoned and reasonable position, but not exactly a TIGGR-ish call to scrap the Article (TIGGR, para 225).

Hogan Lovells also questions whether GDPR is really all that misunderstood and notes the global direction of legislation is towards GDPR, not away from it (our emphasis):

‘6.2 Nonetheless, the existing accountability framework, while still under development in practice, is also well-understood by the majority of organisations. Many organisations have dedicated considerable resources both before and since the GDPR first took effect in May 2018 to develop internal governance programmes that meet the current standards. This is a worldwide phenomenon that is taking place across many different legal cultures that are beyond the scope of application of the GDPR. Therefore the introduction of a new Privacy Management Programme (PMP) requirement needs to be carefully considered against this background.

6.3 Equally, the proposed reforms could potentially give rise to the possibility of diverging standards of accountability between the UK and other jurisdictions that follow the GDPR model. Any degree of divergence that causes inconsistencies among various standards could ultimately be problematic for many organisations (both large and small) that operate across borders, who currently have in place privacy programmes which are implemented in order to comply with various regimes.’

And on transfers, and changes that could jeopardise the adequacy decision, Hogans couldn’t be clearer:

‘6.4 The current proposals, such as removing obligations to perform DPIAs, appoint a DPO and maintain records of processing, may potentially also create the perception within the EU’s institutions that the UK is seeking to lower the standards of accountability. This could be a factor in the European Commission’s determination of whether to renew the UK’s adequacy status in 2025 and therefore the government should take into account this risk.’

‘8.2 The objective should be to increase the number of adequacy decisions that are granted, in the interests of promoting and facilitating the free flow of personal data between countries while retaining the credibility in the adequacy determination process. Therefore, we encourage the UK government and ICO to work with other countries in developing a more risk-based and outcomes-led approach to adequacy decisions. …’

Hogans also offers some additional and interesting angles on, for example, privacy-enhancing technologies and cookies.

BRC

The BRC is the trade association for UK retailers. Their membership ‘comprises over 170 major retailers … plus thousands of smaller, independent retailers through a number of smaller retail Trade Associations that are themselves members of BRC’. Their members deliver ‘an estimated £180bn of retail sales and employ just over 1.5 million colleagues’. They’re both huge numbers.

You might expect retailers to be in favour of loosening up the rules so they’re released to do AI-driven targeting and other snazzy profiling and personalisation. Well, you’d be wrong.

In their response, the BRC lead with protection of the individual (page 4):

‘We welcome the commitment to place the protection of people’s personal data at the heart of any new regime. That is vital to maintain the trust of our customers and data subjects – in turn vital for them agreeing to share their data, and particularly to any desire to have them agree to share it for unconnected purposes.’

And while they’re in favour of resolving cookie fatigue and reducing the burden on business, the BRC have some very clear messages, starting with transfers (page 4):

‘Several of the proposals, however, raise concerns that they do not help sufficiently to overcome the potential threat to adequacy. Some are marginal like prior consultation with the ICO; some like changes to DPOs and DPIAs bear the hallmarks of a substitution of one type of requirement for another very similar but with reduced efficacy and a similar workload; others like breach reporting do not eliminate the need to do the work but eliminate the need to properly report it.’

And their summary on page 5 is so clear, it’s worth repeating a chunk here. Like Bird & Bird and Herbies, they question if the proposals deliver on their rhetoric (our emphasis):

‘However, there seems to be a degree of conflict between some of the statements in the opening parts of the consultation – both in the Introduction and the Minister’s foreword. For example, the Minister states that the UK now has the freedom to make a ‘bold new data regime’ and ‘aspects of the current system remain unnecessarily complex or vague’ after three years. These statements suggest the Government is intent on quite dramatic change. Set against this is the optimistic, perhaps over optimistic, view that there remains a potential for maintaining EU adequacy while making fundamental changes and other changes that may at least be perceived by others – not least those in the European Parliament which often tends to move in a more restrictive way in this space – as fundamental. In reality the question has to be asked: if the changes are just tinkering – why make them if they may undermine the higher prize? The issue goes beyond the EU to whether other jurisdiction[s], many of which follow EU standards, may not recognise our regime for adequacy if the EU does not do so. Issues would then arise for onward transfer mechanisms.

The BRC believes that it is in the interests of business that maintenance of adequacy should be seen as a strong counter-balance to any proposed changes unless and until the EU moves in a direction that so potentially undermines innovation and change and increases burdens unnecessarily that adequacy is no longer sustainable as an objective.’

‘Finally, it needs to be recognised there is a danger that businesses will end up having to operate dual systems – which is not simplification – or simply move to the EU regime as the higher level requirement (and this should be permitted).’

BRC is against removing Article 22 (see para 22), but in favour of clarification – which seems very reasonable.

As to Chapter 2 and the burdens on business, they’re clearly in the ‘show me the money’ camp:

’21. The test for any change is whether or not it leads to acceptable simplification or whether it is in essence the substitution of one untested and new regime for another – a rebrand rather than something new. Overall, while there may be some useful thoughts at the margins, we are not convinced that a wholescale change is necessarily for the better.’

The BRC also don’t agree with the government’s view that GDPR isn’t working, they note that ‘box-ticking’ is more about the organisations not the regime, and they don’t want to jeopardise all the hard work people have put in to get Privacy onto the table in the first place (our emphasis):

’25. To challenge all that risks undermining what has already been built up in favour of a belief that the procedures are not necessary and were too restrictive – even though the outcomes that ought to be produced by the new system often should be the same as before. The overall message to business from the changes, albeit incorrect, would be that data protection is a less important consideration than hitherto.

27. An upheaval could be justified if the current system were not working. We believe that to a large extent it is and that the problems that exist could be overcome by some lesser tweaks. We are not convinced by the suggestion that the current system leads to a box ticking approach – one justification in the consultation for these changes. The best organisations do indeed engage in proactive consideration of their obligations and have in place systems and personnel to oversee compliance.

28. It is true that some may adopt a tick box approach – but that is inevitable with any system where there is such a huge range of diverse businesses that are required to comply. With any system many businesses will want to know what to do and have a list that they can implement so they know they are compliant. That is the case with nearly all regulation – and even more so when the legislation is not prescriptive.’

And on the proposal to remove Article 30 Records of Processing (we’d bold the whole of this but that’d defeat the point, read it and you’ll see):

’47. The removal of a clear record keeping requirements – which would seem to be necessary for an orderly approach to data protection management – and indeed while still requiring the means to meet the requirements of the GDPR for SARS and other information to be kept – seems bizarre. It can only encourage organisations to be less strict about their records and potentially undermine confidence of data subjects should it be found the right records have not been kept.’

We could go on and on – it’s clear and powerful. But now let’s turn to the big one, the UK ICO’s response.

The UK ICO

As the UK’s Data Protection Authority, the UK ICO has a clear interest in the Consultation. The UK ICO’s 89-page response reads easily but was probably not an easy read for the government.

It’s very diplomatic, as to be expected, and the ICO is good on several items (subject to seeing more detail) including reviewing the level of risk justifying breach notification to the regulator, bringing PECR’s enforcement into line with GDPR, and replacing the corporation sole with a board and CEO (all of which we also agree with), but it’s clear that the ICO has a number of deeply-felt problems with the proposal. Other than schooling the government on anonymisation, we think the following parts are most telling.

Thin

Throughout its response, the ICO caveats any support for proposals with the need to see more analysis, proof, and detail on the proposals and related safeguards. For example, in discussing Privacy management programmes (PMPs), in para 58 the ICO states it’s position very clearly:

‘However, we think there is still more work for Government to do to set out whether the additional benefits that a PMP approach would bring would outweigh the potential costs involved in making these changes. We also encourage Government to explore whether these benefits could be achieved with more minor changes to the level of prescription in current accountability requirements, avoiding the potential disruption that could come with more substantial change. ‘

Interestingly, the ICO seems pretty relaxed to discuss abolishing Article 30 Records (paras 70-71) even though it states: ‘Keeping good records is a key element of good privacy management and high standards of privacy.’

Transfers

Transfers has to be one of the key topics in this Consultation and it barges in on the Exec Summary:

‘Our engagement with stakeholders has also made it clear they welcome the certainty and seamless data flows with our major trading partners positive adequacy decisions provide, alongside the potential benefits of domestic legislative reform. This highlights the importance of ensuring any proposed reforms deliver specific and tangible benefits whilst safeguarding high standards of data protection.’

And the proposals on transfers are dealt with fully in paras 115 – 158. The ICO’s position is perhaps clear from two statements, in paras 117 and 122 (our emphasis):

‘UK businesses also rely on the ability to import and export data in a fast-moving global digital economy. For this reason, the certainty that is provided by the EU’s positive adequacy decision on the UK’s laws has been welcomed by businesses of all sizes in the UK. This decision allows UK firms to continue to import and export data to the EU without further safeguards needing to be put in place. For exporting personal data to other territories, organisations expect to be able to employ risk-based and practical ways to transfer personal data across the world and know how to achieve compliance with our standards.’

‘Stakeholders, particularly UK businesses, have also consistently stressed to the ICO how important it is for them to secure and retain the UK’s adequacy status with the EU. Therefore, any reform of the process to assess and grant adequacy to other countries and jurisdictions should take into account the importance to UK business of retaining our EU adequacy status.‘

DSARs

The ICO is clearly against anything that reduces the ability for, or dis-incentivises Jo Public from making a data subject request. The government’s proposals for a fee and a ‘cost cap’ are cautiously handled on that basis.

DPIAs & consulting the ICO

The ICO sets out compelling arguments to retain the DPIA, which the government want to do away with. On a related topic, the ICO recognises that not many people consult the ICO on high risk processing, but is keen to retain that requirement.

Fairness, AI & Art 22 automated decision-making

The proposals on fairness and Artificial Intelligence (AI) clearly set things off for the ICO – quite understandably. We agree with their comments here, as we agree with almost all of their response. The ICO also takes the proposal to task on TIGGR’s idea of deleting Article 22’s provisions on automated decision-making, which include the right to human review. In a passionate and clear passage, the ICO makes it clear that humans come before machines, and the human review should not only stay, but Art 22 should be extended to hybrid decisions with some human element ‘but the decision is still significantly shaped by AI or other automated systems‘.

Political use

The government wants to free up how political parties can make use of personal data, in the name of democracy. Some proposals, such as extending the soft opt-in, make sense. But the ICO gives this topic comparatively lengthy treatment (paras 103 – 109), noting the complaints it’s received about political use and the frustration this could cause if appropriate safeguards aren’t in place.

ICO’s Independence

The ICO (quiet appropriately in our view) raises red flags on the government having greater powers to tell it what to do, power to appoint it’s CEO, and power of veto over ICO Guidelines. The ICO cites Convention 108+ in support, which states that regulators shall be independent and ‘shall neither seek nor accept instructions.’

As the ICO notes (page 4):

‘Despite this broad support for the proposals to reform the ICO’s constitution, there are some important specific proposals where I have strong concerns because of their risk to regulatory independence.’

‘However, some of the proposals risk undermining the independence we need to carry out our responsibilities under both data protection and freedom of information legislation to oversee government and the public sector.’

The Independent Commissioner for Biometrics and Surveillance Cameras

One of the proposals is to absorb the two roles of The Independent Commissioner for Biometrics and Surveillance Cameras into the ICO. The Biometrics role was separate to the Surveillance Cameras role, but are now joined into the one appointment, that of Professor Fraser Sampson.

Professor Sampson has published a press release and a very well-reasoned response to the DCMS Consultation. Surprisingly (and to him), Professor Sampson wasn’t informed that his two roles were up for absorption into the ICO – which clearly and justifiably rankles (para 2.2):

‘On 10 September 2021, the government announced this consultation on data reform. Until it was brought to my attention privately, I had been wholly unaware of the consultation or the fact that it was to contain a question about the transfer of functions to the ICO. At the time of writing I have yet to receive formal notification as a statutory officeholder but, notwithstanding that formality, I have had the advantage of seeing the letter sent to other stakeholders and have met with officials and the Minister for the Lords for which opportunities I am grateful.’

And the Professor drops an interesting insight in para 2.4 (our emphasis):

‘Crucially I have received a categorical assurance from ministers that the purpose of the consultation questions is to enable the proper formulation of as yet undecided policy in light of informed responses. It is on that understanding that I submit this one.’

We highly recommend reading Professor Sampson’s response, which is very persuasive and informative on these two roles – and perhaps highlights the danger of cramming various superficially-convincing proposals into a document. The response demonstrates that behind every proposal are layers upon layers of considerations.

For the Biometrics Commissioner aspects, the position seem much clearer:

- the ICO is a regulator,

- the Biometrics Commissioner is not, it’s quasi-judicial and if it’s going to be absorbed, the Investigatory Powers Commissioner is a better place.

This is powerfully noted in section 9 of his response and para 9.2 in particular (our emphasis):

‘As discussed above, the principal functions of the Biometrics Commissioner are quasi-judicial in nature and are exercised in the setting of policing, counter-terrorism and national security. To characterise them as upholding information rights is to miss this fundamental point and their absorption would introduce a UK regulator to this area and then require that regulator to take on non-regulatory judicial functions. In the setting of those functions there may also be an inherent conflict for the ICO as they will find themselves participating in decisions to authorise police retention of biometrics which are later challenged by the individual who would not then be able to turn to them as the nation’s regulator upholding their information rights at large.’

And Professor Sampson makes a clear case that ‘while they involve oversight of the lawful processing (including retention and sharing) of some highly sensitive personal data, the functions of the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner go far beyond data protection.’

Our Founder’s Response

Robert Baugh, our Founder & CEO, filed a personal response to the Consultation, which received an impressive amount of engagement on LinkedIn from data protection professionals. His view on switching from one regime to another with dubious benefits echoes those above. His summary includes a consideration of the recent years’ uncertainty driven by Brexit and the winding road to adequacy, the current economic context, his view that the Consultation is bias against the EU GDPR, and is incorrect in its understanding of how well GDPR is understood and Privacy governance is handled in practice. His detailed response runs to 42 pages.

What’s Keepabl’s position?

You can probably guess by now!

To draw an analogy from the world of Security, imagine the UK said that ISO 27001 and SOC 2 were to be banned from the UK and that the UK government was going to create a Security standard that eclipsed them both. It would include making an inventory of your assets, assessing risks, training, incident response, escalation, audits, record-keeping, and clear responsibilities – indeed all the hallmarks of a Security standard. The reason was that British organisations would finally be free to break the chains and determine their own way to address Security risks and obligations. And the UK Security standard would be the beacon for the world to follow. First, does that make sense to you, given the status of 27001 and SOC? And where do you think British businesses would look for examples of how to deal with Security? Second, it’d have to be pretty ground-breaking to achieve sufficient benefit to rock that boat.

As a SaaS provider, we can provide the same benchmarking, assistance and reporting for any Privacy or Security regime. So, whether it’s GDPR or something else really doesn’t matter to us per se, what matters is helping our customers.

As a growth tech company, we strongly believe in collaboration and sharing, and in continual inquisitiveness, improvement and innovation for the greater good (and hopefully our own along the way).

Selfishly, and for our customers, we’re in favour of anything that removes barriers, increases harmonisation, creates certainty for planning and execution, reduces red tape, and irons out the differences in doing business that put speed bumps or road blocks in the way of international trade.

We don’t see the DCMS proposals passing these tests. In terms of the obligations on business, they’re mostly tweaks with little to no impact. They’re almost entirely to the detriment of individuals, some dangerously so. If the ground-breaking magic that delivers enormous benefit to British organisations is there, we’ve missed it. We believe the proposals have the potential to cause significant issues for the UK’s relationship with the EEA. This is unwelcome in the context of Britain’s immediate and near-term economic context.

There are 2 specific aspects on Privacy management that we agree deserve consideration (on clarifying when a breach needs notification to regulators and on the role of the DPO), where we believe iterative improvements can be made without impacting individuals. Bringing PECR enforcement into line with GDPR would be a clear win but that’s hardly a revolutionary reform to set Britain apart. The set of proposals on the UK ICO have one clear improvement (a board with a CEO, instead of a corporation sole) but include concerning proposals for government control of an independent regulator – and again, these don’t deliver simplicity for organisations nor arguably any competitive advantage.

Related Articles

Blog News & Awards

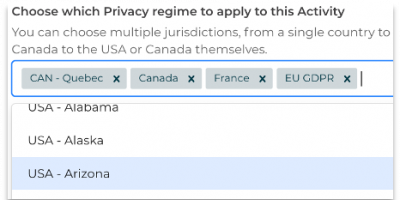

Choose any Privacy Jurisdiction with Keepabl’s Internationalised RoPA

We’re delighted to announce, as part of our internationalisation and to better support customers worldwide, that we’ve updated our RoPA and Data Map solution so you can now select ANY…

Blog

EU GDPR Adequacy Decision for EU-USA DPF

10 July 2023: EC adopts adequacy decision for the EU-US Data Privacy Framework! Here’s the announcement and here’s the 137-page DPF adequacy decision. The decision concludes that the United States…