GDPR's 2nd anniversary

As it enters the 'terrible twos' what's next for GDPR?

GDPR’s just turned 2 – here’s our overview

25 May 2020 went past with a whisper compared to 25 May 2018. GDPR entered the ‘terrible two’s at a time when how we work has been forcibly and massively changed by events that even pushed ever-present Brexit off the news cycle for a few months.

We take a look at what we’ve learned, heard and observed about GDPR over the last 2 years and take a looking glass to the near future.

Most scorecards aren’t that great

First, the good stuff. The European Data Protection Board‘s input to GDPR’s review starts glowingly:

‘The application of the GDPR in this first year and a half has been successful. The GDPR has strengthened data protection as a fundamental right and harmonized the interpretation of data protection principles. Data subject rights have been reinforced and data subjects are increasingly aware of the modalities to exercise their data protection rights. … The GDPR also contributes to an increased global visibility of the EU legal framework and is being considered a model outside of the EU.’

The European Commission’s statement on GDPR’s 2nd anniversary rightly notes that: ‘Within two years, [GDPR’s] rules have not only shaped the way we deal with our personal data in Europe, but has also become a reference point at global level on privacy‘.

You’ll easily find many similar reviews, including from industry representatives such as Digital Europe, the trade association representing digitally transforming industries in Europe: ‘The GDPR has increased accountability and has resulted in greater awareness of data protection issues at all levels.’

While this is true, and to be applauded, the scorecards are generally mixed at best. Even the European Commission’s statement goes on to implicitly acknowledge the 3 biggest complaints.

Level of compliance

The Commission diplomatically recognises the slow move to compliance: ‘Nonetheless, compliance is a dynamic process and does not happen overnight.’

You can see this in many surveys. One that we think was more accurate, based on our interaction with organisations, was the Capgemini survey reporting that 28% of organisations felt they were compliant in June 2019 (compared to 78% who thought they would be by May 2018).

A discussion on why, has to start with the wording of GDPR itself.

Complexity

GDPR’s a complex, long and ambiguous law, which makes applying it hard for organisations – and in some areas even for Privacy professionals.

This was brutally recognised, for example, by a July 2019 study prepared for the European Parliament on GDPR and Blockchain, where the author states (our emphasis):

‘… , examining this technology [blockchain] through the lens of the GDPR also highlights significant conceptual uncertainties in relation to the regulation that are of a relevance that significantly exceeds the specific blockchain context. Indeed, the analysis below will show that the lack of legal certainty pertaining to numerous concepts of the GDPR makes it hard to determine how the latter should apply both to this technology and to others.‘

One example area that we believe has yet to make its impact fully felt, is joint controllers. Under GDPR, particularly after recent case law, this has created a very complex, technical area with very real potential negative impacts for well-meaning but under-resourced organisations already struggling with core compliance issues. Consistency is absolutely key in how DPAs and courts interpret GDPR and, as we’ll see below, this isn’t always happening.

Burden on SMEs – the 99%

Also in mid-2019, the Commission’s Expert Group to support the application of the GDPR delivered its 1st Year Report – and it wasn’t pretty, raising the same issues in the 1st anniversary as many raise today (see our summary.) We’ll pick out one quote while we’re on complexity:

‘Many SMEs mention they had to seek advice from external consultants to understand the rules and set up systems to comply with the GDPR (including the implementation of technical and organisational measures), and that they usually lack the necessary human and economic resources to implement the obligations in GDPR.’

The EDPB recognises the struggle, particularly for SMEs:

‘The EDPB acknowledges that the implementation of the GDPR has been challenging, especially for small actors, most notably SMEs. [DPAs] have been developing several tools to support SMEs in complying with the GDPR. The EDPB is committed to facilitating the development of these tools in order to further alleviate the administrative burden.’

One way to resolve those ambiguities in year 2 was for consistent implementation and interpretation – the harmonisation that GDPR was all about. However, many feel this is a current major flaw.

Harmonisation & clarity

The Commission’s statement recognises the importance here: ‘Our key priority for the months to come is to continue ensuring the proper and uniform implementation of GDPR in the Member States.‘

Unsurprisingly, organisations promoting human rights and freedoms such as Privacy International and EDRi put this most strongly: ‘EDRi is deeply concerned by the way most Member States have implemented the derogations, undermining the GDPR protections and by the misuses of GDPR by some DPAs.’

Industry is equally concerned as they try to implement Privacy Governance. Digital Europe gives some practical examples:

‘DPAs continue to issue national guidelines on the same topic, leading to contradictory results …’, ‘Currently there seems to be no clear and consistent approach to data protection impact assessments (DPIAs). … For example, different national lists of when a DPIA is required have led to unrealistic and unmanageable expectations for organisations.’

DPIAs is a classic example where Data Protection Authorities aren’t acting as one, as we set out in this post, and it leads us to another key difficulty.

Over-reaching by Regulators

We’ve always said the UK ICO is a great regulator in an imperfect world, working hard to educate business and help with practical guidance – and we continue to believe that. While we generally agree with their guidance and interpretation of GDPR, like the Article 29 Working Party, EDPB and others, they’re not immune from occasionally taking a position that’s perhaps more in-line with where they wish the law to be than where the law actually is.

Not so well-known before GDPR, DPAs have certainly had their 2 years in the sun. The UK ICO and A29WP/EDPB have generally been excellent (in our view, which some may not agree with) but this over-reaching tendency has to be carefully watched for across all Privacy regulators going forward.

Two examples:

- DPIAs: As outlined above, this area still suffers from DPAs issuing guidance that requires DPIAs – or implies DPIAs are required – in cases well beyond GDPR’s test. We’re a fan of DPIAs and recommend doing as many as practicable, but the inconsistency of guidance and yardsticks is not helpful.

- EU Representatives: The EDPB’s draft Guidance on GDPR’s Territorial Scope published for consultation made an EU Representative inherit full liability for the controllers and processors it represented, in a single paragraph with no legal basis, thrown in at the end of an othewise lucid and reasonable legal analysis on scope. At a single stroke, this would have greatly reduced the number of people and organisations willing to take on the role, defeating practical compliance. Happily, the Guidance published after consultation correctly rowed back this position.

This over-reach is visible across several areas of GDPR, and e-Privacy, and is particularly unhelpful given the already high bar that GDPR sets and that many are still not reaching.

As Digital Europe notes:

‘We see a clear tendency from DPAs and the EDPB to put forward an overly restrictive interpretation of the legal framework, in some instances going against the letter and spirit of the GDPR text or relevant case law. As a consequence, innovation in Europe today is risky and investment into new or improved products and services is stymied.’

And, as just one of the examples they give:

‘By contrast, we are seeing unduly restrictive national interpretations of legitimate interest that rule out reliance on this legal basis for purely commercial interests. This is contrary, for example, to the GDPR’s Recital 47, where direct marketing (but one case of commercial interests) is set forth as an example of valid use of legitimate interest.’

All of this uncertainty not only makes compliance appear too difficult – it makes regulatory enforcement seem a distant possibility. Which brings us to the third major complaint – although perhaps not from business!

Lack of enforcement

It’s perhaps sad that we need lots of enforcement action for many organisations to move faster to compliance, but that seems to be the case here. On the organisation’s side, this may be due to the decades of inertia due to the 1998 Act’s low levels of fines.

But on the regulators’ side, enforcement needs to be resourced and the EDPB itself:

‘notes that most of the [DPAs] state that resources made available to them are insufficient. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that all [DPAs] are provided with sufficient resources by the Member States to carry out their tasks.’

The European Commission also recognises this:

‘The national data protection authorities, as the competent authorities to enforce data protection rules, have often not yet reached their full capacities. We therefore call upon Member States to equip their data protection authorities with the adequate human, financial and technical resource to make effective use of their enforcement powers.’

As Privacy International notes: ‘Two years on our main concern is the lack of implementation of GDPR and the enforcement gap. Our work shows numerous infringements of GDPR but controllers are not being sufficiently held to account.’

What now?

The GDPR has undoubtedly rebooted Data Protection in the EEA and across the globe, particularly in the USA. It’s unreasonable to expect (then) 31 Member States to come up with a unified position, given the differences in where each was coming from.

In that context, GDPR is a huge success. It’s a very welcome law, ably updating the balance of protecting individuals and the need to share and use personal data in today’s digital world. While the above criticisms, and more, have to be addressed, there is much to be positive about and much that can be done to help lift compliance.

Modification

We agree with the EDPB that: ‘after only 20 months of GDPR application, the EDPB takes a positive view of the implementation of the GDPR and is of the opinion that it is premature to revise the legislative text at this point in time.’

However, we do think that there is a need to review the approach regulators take in certain areas, which has sometimes become over-reaching, which leads us to Guidance.

Guidance

Going forward, it’s good to see the EDPB committed to helping reduce the ‘administrative burden’ of GDPR compliance. It must drive guidance that satisfies tough criteria:

- conclusive, leaving as little doubt as possible,

- practical, focussed on achievable compliance with clear examples, aware of real-life impacts and challenges and taking account more of the ‘policy view’, as legal courts often do, and

- limited to what GDPR says, not what regulators’ perhaps natural inclinations might be. This is no time for land-grabbing, GDPR already expanded the enclosures. We need simplification and certainty based strictly on GDPR and practical compliance.

e-Privacy Regulation

Along with Privacy International, EDRi – and almost everyone we speak to – we join the EDPB in calling on EU legislators:

‘in particular the European Commission, to intensify efforts towards the adoption of an ePrivacy Regulation to complete the EU framework for data protection and confidentiality of communications.’

The level of confusion, in particular around e-Privacy and cookie-type technologies, is very damaging as it reinforces the feeling that compliance is too difficult to tackle now. As a simple example, whether you see the IAPP’s table on the treatment of cookies by French, UK, German and Spanish authorities as showing large or only small variations, ideally there shouldn’t be such a table. Harmonised rules will be a great benefit.

Brexit

31 December 2020, the end of the transition period, is rapidly approaching. It would be very helpful to have an adequacy decision for the UK before year end. While we recognise some valid points remain, at a policy level, given the UK’s position on the assessment criteria compared to some of those who already have adequacy decisions – and indeed some Member States who don’t need one – in practice, it would be ludicrous not to grant an adequacy decision.

The UK has already passed legislation to adopt the EU GDPR as the UK GDPR, so the law will be exactly perfect in that regard, and GDPR-style protection will continue in the UK regardless of an adequacy decision, so at least organisations can be confident that their investment in EU GDPR compliance will bear fruit for UK GDPR compliance, which is a positive to hold onto!

Related Articles

Blog

2025: Keepabl's Year In Review

As we look at an exciting roadmap for 2026, it’s cliched to say, but where has the past year gone? 2025 delivered another year of strong product growth, delivering continually…

Blog

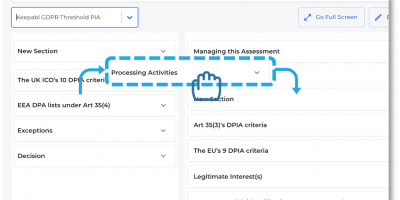

Build Your Own Assessments in Keepabl!

We’re delighted to announce that Template Builder is now live in Keepabl, rounding out our awesome Assessments module. With our Assessments Template Builder you can: Build ANY Assessment you want…