The Spice Girls & the 2021 ‘NHS Big Data Grab’ - UPDATED 220821

A brief history of Data Security, Privacy and Sharing in the NHS

On 12 May 2021, the NHS announced the ‘General Practice Data for Planning and Research (GPDPR)’, daily collection of GP data to support vital health and care planning and research – including sharing with commercial entities.

Controversially, the NHS gave people less than 2 months, until late June 2021, to opt out. And opt-outs were confusing, they had to be done in two different ways, one with your GP and one with the NHS.

Public outcry ensued. The deadline to opt-out was pushed back to the end of August 2021.

How did this happen? Just a few months before, in December 2020, at the end of her term as the highly-respected National Data Guardian, Dame Fiona Caldicott had released a new, 8th ‘Caldicott Principle’ ‘to ensure no surprises for patients and service users’ about how their confidential information is used.

People had been pretty surprised, to say the least.

UPDATE 22 AUGUST 2021 – In June 2021, the opt-out deadline was pushed back to September 2021. The program was then suspended and, in a letter of 19 July 2021, the Health Secretary confirmed there was no date set for data collection to resume, and that it would not resume until the following was in place:

- ‘the ability to delete data if patients choose to opt-out of sharing their GP data with NHS Digital, even if this is after their data has been uploaded, [Note: it’s surprising this wasn’t already in place.]

- the backlog of opt-outs has been fully cleared, [Note: in May 2021, 107,429 people opted out, followed by a huge 1,275,153 in June 2021.’]

- a Trusted Research Environment has been developed and implemented in NHS Digital,

- patients have been made more aware of the scheme through a campaign of engagement and communication.’

The letter is worth reading in full. And read on below, to see how this may have been a predictable outcome.

Spice Girls & Steve Jobs

Image credit: Stephen Hackett, https://512pixels.net/projects/imacg3/

To see this in context, we need to go back to 1997, before the GDPR, before even the 1998 UK Data Protection Act (implementing the 1995 EU Data Protection Directive), to the days of the 1984 UK Data Protection Act, to the year the Spice Girls had the most number 1 hits in the UK charts and a good year before Steve Jobs introduced the iMac.

It’s easy to forget there was a time when NHS doctors and consultants wrote comments by hand onto medical records or letters referring patients. That started to change in earnest in 2002. But the technology-age focus on trust in the NHS’s handling of patient data started before that, with the famous Caldicott Committee in 1997.

It’s a huge and detailed history, so we’ll rattle through it at a page-turning rate and give you jumping off points to learn more because that’s what you want, what you really, really want…

A History of Success & Failure

There have been some undoubted digitisation and data sharing successes in the NHS, such as Spine, the digital central point which allows information to be shared securely through national services and ‘supports the IT infrastructure for health and social care in England, joining together over 23,000 healthcare IT systems in 20,500 organisations’.

There have also been well-documented failures and well-known and well-respected Guidelines as a result.

Let’s start with a couple of resounding successes:

- Caldicott Principles and

- Caldicott Guardians.

1997: Caldicott 1: Concern over NHS data sharing & technology advances

The first Caldicott Committee reported in December 1997. The Caldicott Committee’s Review of Patient-Identifiable Information, and the long-lasting principles and roles it created, were named after its phenomenal leader, Dame Fiona Caldicott.

For our story, it’s key to note that the Review was commissioned (our emphasis) ‘by the Chief Medical Officer of England owing to increasing concern about the ways in which patient information is used in the NHS in England and Wales and the need to ensure that confidentiality is not undermined. Such concern was largely due to the development of information technology in the service, and its capacity to disseminate information about patients rapidly and extensively.’

The public has always trusted the NHS in terms of medical skill and dedication. But in 1997, there were clear concerns about how the NHS handled patient data from a Security, Privacy and Sharing viewpoint.

Reflecting this, the Caldicott Review’s remit was focused on sharing for purposes other than direct care, medical research or under a statutory requirement.

‘Caldicott 1’ identified over 80 such data flows (at a strategic level), looked at the purpose of each, and happily found they were all justifiable in the then-current policy.

However it did find ‘a general lack of awareness throughout the NHS at all levels of existing guidance on confidentiality and security, increasing the risk of error or misuse. Problems posed by poor access controls were identified. The Recommendations proposed in this Report are designed to focus attention on the procedures and systems where we identified a weakness, and to propose solutions.’

Those solutions included 16 recommendations, including:

- the original 6 ‘Caldicott Principles’ to help guide the NHS in its data handling, and

- creation of ‘Caldicott Guardians’, a senior person, expected to be a health professional, to have ‘responsibility for safeguarding confidentiality of data flows … for ensuring that where there is scope for local flexibility, the purposes for which patient information is used within an organisation are robustly justified, that the minimum necessary information is used in each case and that good practice and security principles are adhered to.’

Caldicott Guardians have been required for NHS organisations since 1998, and for local authorities with adult social care responsibilities since 2002. There are over 18,000 Caldicott Guardians in post today.

It was good to have the Caldicott Principles and Guardians. Particularly as the UK was about to embark on the most complex healthcare IT programme the world had ever seen…

2002: The National Programme for Information Technology in the NHS (NPIT)

It would be hard to argue with the underlying vision for the NPIT: ‘to use IT to create a fully integrated electronic patient record that could be securely accessed by connecting GP, Community Health, Mental Health and Acute care settings and by enabling patients to exercise choice.’

But it was incredibly ambitious. As the NAO had said in 2006, ‘The Programme’s scope, vision and complexity is wider and more extensive than any ongoing or planned healthcare IT programme in the world, and it represents the largest single IT investment in the UK to date.’

To say it didn’t go smoothly is an understatement.

By 2011, as the Major Projects Authority (MPA)’s review noted, it had been ‘criticised as ambitious and unwieldy; poorly served from over-selling and over-promising by suppliers; and not providing clear value for money (NAO Report May 2011). It has also not delivered in line with the original intent as targets on dates, functionality, usage and levels of benefit have been delayed and reduced. The suppliers for 3/5th of the country in terms of local service provision have exited their contractual terms or had their contract terminated leaving at least one significant dispute.’

But it wasn’t all failure, as the MPA also noted, referring to Spine and other systems and services that had become ‘business as usual and form essential infrastructure’.

Targeted at costing £2.3bn over 3 years, the NAO’s revised forecast of the cost in 2011 was £11.4bn. That year, with costs suggested to be up to £12.7bn, the programme was shut down. The successes pointed out by MPA represented around £2bn of the expenditure to March 2011.

Undeterred, the UK Government was raring for another go, this time with a project to combine GP and other health records and make them available for commercial and non-commercial research subject to an opt-out, resulting in headlines that ‘40 per cent of GPs plan to opt out of the NHS Big Data Sweep, due to a lack of confidence in the project’.

Sound familiar? It’s not 2021, but 2013.

2013: care.data

In 2013, the NHS launched a program called care.data, essentially to do what the GPDPR wants to do in 2021: combine your GP and other NHS records for direct patient care and other reasons, including research by commercial entities.

It caused the same level of controversy as the 2021 announcement. And it ran smack into a 2013 update of the Caldicott Principles.

2013: Caldicott2

No typo, it’s written without a space: Caldicott2 was a 2013 follow-up report into Information Governance in the NHS, with the ‘overarching aim … to ensure that there is an appropriate balance between the protection of the patient or user’s information, and the use and sharing of such information to improve care.’

In a statement of great interest to Privacy practitioners tracking the history of adoption and public opinion, Dame Caldicott’s report stated that, while the Caldicott Principles were still found very useful, the ‘original report was written in 1997 when the service was more paternalistic and much less patient centred. Now citizens are a lot more concerned about what happens to their information; who has access to it, for what purposes is it used, and why isn’t it shared more frequently when common sense tells them that it should be.’

And in statements very relevant to today’s arguments, she noted (our emphasis):

‘Patients are generally keen to contribute to research but do want their consent obtained appropriately.’

‘If data clearly identifies individuals, it must not be processed without a clear legal basis. If data is anonymised in line with the ICO’s anonymisation code, it can be freely processed and publicly disclosed. However, there is a third class of data, which is of great interest to researchers, that on its own does not identify individuals, but could do so if it were to be linked to other information. This ‘grey area’ includes data that has been de-identified by the use of pseudonyms or coded references, but could be re-identified when combined with other data.’

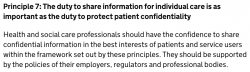

The 7th Caldicott Principle: Sharing

Caldicott2 added a 7th Caldicott Principle, on Sharing:

This duty to share was put into section 3 of the Health and Social Care (Safety and Quality) Act 2015 but, importantly, it is limited to situations where the disclosure is ‘likely to facilitate the provision to the individual of health services or adult social care in England, and in the individual’s best interests.’

2014: Back to care.data

care.data was against the ropes and, in January / February 2014 the NHS sent out a leaflet to every household in England to promote the project, which today may have been criticised for ‘dark patterns’.

The leaflet was indeed heavily criticised and, in 2014, care.data was paused. It had a slight revival in 2015, but The Guardian reported: ‘In a damning assessment, the Major Projects Authority said both care.data – a plan to link and store all patient data in a single database – and NHS Choices – the website supposed to allow users to log in and access medical services – had “major issues with project definition, schedule, budget, quality and/or benefits delivery, which at this stage do not appear to be manageable or resolvable”.’

The Guardian went on: ‘The assessment by the MPA, which was created by the Cabinet Office and Treasury to oversee big projects, amounts to a rebuke of Tim Kelsey, NHS England’s data tsar and a former Sunday Times journalist who is seen as close to David Cameron.’ Again, ring any bells? Plus ca change…

We’re up to 7 years ago, time to speed up.

2016: Caldicott3

Dame Caldicott published The Review of Data Security, Consent and Opt-outs in July 2016, responding to a joint instruction from the UK Health Secretary for the Care Quality Commission (CQC) to review data security in the NHS and for the National Data Guardian (then Dame Caldicott) to develop new data security standards, a method for testing compliance against these, and for a new consent model for data sharing in the NHS and social care.

Thought your job was tough?

In a joint letter to the Health Secretary, the CQC and NDG set out:

- 13 recommendations on Data Security,

- 11 recommendations on consent / opt-outs, and

- an 8-point consent / opt-outs model (note the word consent).

On consent / opt-outs, the first 2 points were (our emphasis):

‘14. The case for data sharing still needs to be made to the public, and all health, social care, research and public organisations should share responsibility for making that case.

15. There should be a new consent / opt-out model to allow people to opt out of their personal confidential data being used for purposes beyond their direct care. This would apply unless there is a mandatory legal requirement or an overriding public interest.’

While Caldicott3 had not been asked to look at care.data, it noted:

‘The care.data programme, which was due to start extraction in spring 2014, was paused on 18 February 2014 after criticism from the Royal College of General Practitioners, the British Medical Association, Healthwatch England and others.’ and recommended, ‘In the light of the Review, the Government should consider the future of the care.data programme.’

Shortly after Caldicott3, NHS England shut down care.data.

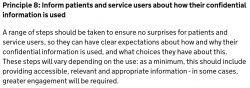

2020: The 8th Caldicott Principle, No Surprises

In 2020, in the last months of Dame Caldicott’s tenure as National Data Guardian, she published the outcome of consultation on the Caldicott Principles, resulting in a new 8th principle.

84% of respondents agreed that this new Sharing Principle should be introduced (10.5% disagreed).

No surprises for patients …

Which brings us to our starting place, May 2021: a ‘new’ program to process and share patient data, with a short period to opt out, not in, surprising the population and leading to the NHS pushing out the deadline.

What did Dame Caldicott do?

Dame Caldicott’s Reports, Reviews, Principles and Guardians all carry a strong governance message, and the importance of building trust was ever-present. Her 2016 Review clearly stated that the case for sharing had not been made to the public. (This author has seen no real communications to build that trust since, being as surprised in May 2021 as anyone else).

However, in a statement in December 2020, she revealed she’d decided not to opt-out.

There’s more

Of course, we’ve only scratched the surface. We’ve not mentioned the IG Toolkit, replaced by the NHS Data Security and Protection Toolkit in 2018 as a result of Dame Caldicott’s work, and revised with a self-assessment deadline of 30 June 2021 (Keepabl have produced a Guide on the Toolkit, changes, and the Privacy aspect).

![]()

And we haven’t gone into the exemptions (for example, the National Data Opt-Out does not apply to disclosure of confidential patient information if it is being used to protect public health) and statutory exemptions such as Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006.

But we hope that’s given you a good context for looking at the current discussions.

The Way Forward

The NHS is deservedly loved for its heart and its medical prowess. It’s also famous for its management labyrinth and for continual government tinkering and wholesale interference. Dame Caldicott was a giant in Information Governance, leaving an incredible, balanced, considered, patient-first legacy for all in Information Governance. The key to resolving the Government’s wishes and the public’s concerns no doubt lies in the Caldicott Principles, the reports they came from, and that focus on trust.

Related Articles

Blog

Privacy fines outweigh Finance fines

This article was first published in Thomson Reuters Regulatory Intelligence on 6 November 2023 and is the personal view of the author, Robert Baugh. Subscribers link. Free trial link. A potentially…

Blog

Cordium & Keepabl: Benchmark GDPR regulatory readiness

Our latest Cordium Insights webinar outlines: best practices for assessing data processing, storage, and protection policies, tips for identifying and remediating control gaps and weakness and on how to develop…